Tackling the Western Water Crisis

By Jason Lee, Director

Climate change is a challenge facing the entire globe, but its impacts are felt differently across countries and regions. In the American west, climate change is intersecting with and exacerbating historic drought, creating a particularly acute crisis in need of immediate attention.

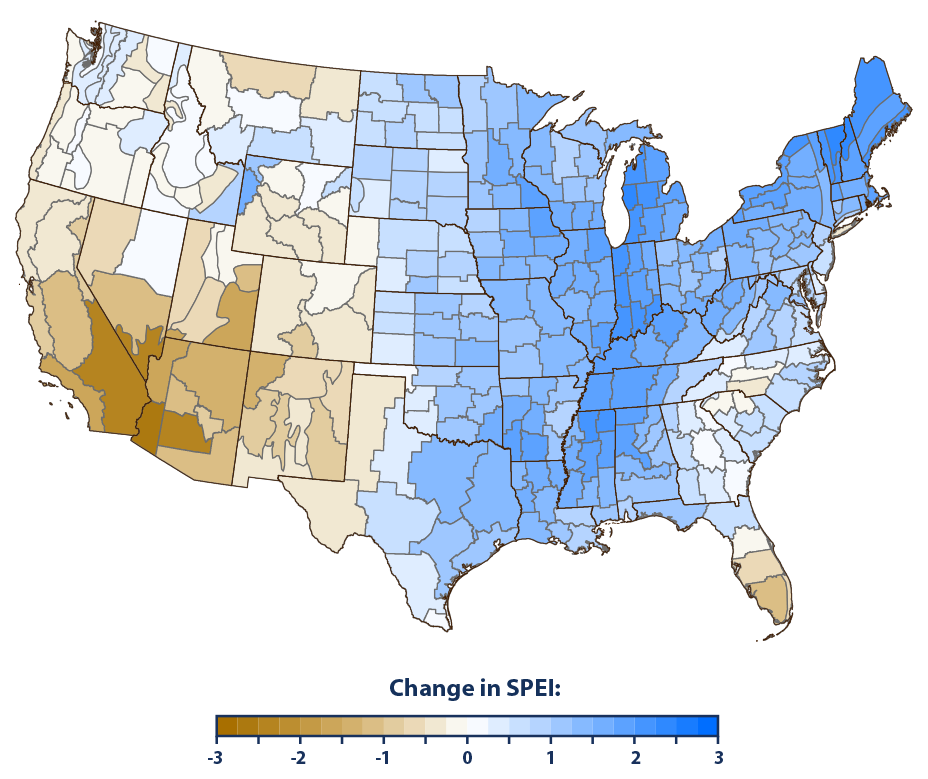

During the past 20 years, the west has been hotter and drier than historical indicators would predict (see charts below). These conditions affect millions of people across all communities—urban, rural, tribal, and suburban—in the western U.S.

Figure 1. Average Change in Drought (Five-Year SPEI) in the Contiguous 48 States, 1900–2020 (source: U.S. EPA)

Figure 2. Average Temperatures in the Southwestern United States, 2000–2020 Versus Long-Term Average (Source: U.S. EPA)

With water resources becoming more scarce and unpredictable, the traditional systems of natural resource allocation have become strained. Urban and suburban populations, outgrowing their historical water resource portfolios, are increasingly looking to acquire or develop water from nearby. Agricultural producers face either rising uncertainty or costs to water their full acreage, leading many to wonder about the future of small agricultural communities, and some to secretly wonder whether it’s smart to cash out their water rights to property developers.

This urban-rural water supply tug of war will become more frequent in an increasingly arid West. Cities and rural communities alike must take action on locally-driven solutions to protect the economy, environment, food systems, public health, and critical infrastructure. While this work is not easy, there are paths forward that can produce better outcomes for all parties. We are committed to working with public and private partners across the American west to develop, capitalize, and deploy these solutions.

A Novel Groundwater Easement that Responds to Local Drought Conditions

Texas was one of the fastest growing states of the last two decades, expanding from about 21 million residents in 2000 to almost 30 million in 2021. Four counties in Central Texas keenly felt the changes brought on by this growth. Comal, Hays, Travis, and Williamson counties form a corridor linking Austin and San Antonio. Their populations collectively grew 92% in the last 20 years, and three of these counties were among the top 4 fastest growing counties in the country since 2010. This put tremendous pressure on the generational ranches and farmlands that form the famous Hill Country of Central Texas, and on regional water supplies, particularly the Edwards Aquifer.

During the past 18 months, we worked with the Edwards Aquifer Authority (EAA) in Texas to create and launch a new program that promotes the long-term sustainability of both the aquifer and local agriculture. The program utilizes a novel kind of easement placed on the groundwater use right itself. The easement toggles use rights according to aquifer conditions, forming a partnership between the Authority as a groundwater management agency and agricultural water users.

Enrollees, who are water users with a groundwater use right on the Edwards Aquifer, are paid a lump sum upfront by the EAA for selling the easement and are entitled to benefit from any periodic revenue-sharing dividends distributed by EAA for participating in the program. Importantly, not only do water users retain ownership of the water right itself, but the easement is designed to give them use rights in the large majority of water years. Only in specific cases, when aquifer conditions are approaching or in drought, does the EAA gain the first option of whether the groundwater use right will be leased back into the open market or enter forbearance. The figure below and the associated video outline the various scenarios in greater depth.

Figure 3. The novel groundwater management easement we designed with the Edwards Aquifer Authority describes program actions under each aquifer scenario.

This particular method of water control costs about a quarter of what it would cost to “buy and dry,” which is an outright purchase of water for non-agricultural purposes that can unintentionally harm local communities, economies, and food production. The ground water easement approach we developed with EAA is a flexible tool made for a climate future that demands faster, more responsive decision making about water resources and new pathways to win-win solutions.

This aquifer-responsive easement design is something that we're very excited to have developed with the Edwards Aquifer Authority and are eager to build on with other partners throughout the American west.

Watch Video: Jason Lee describes our work with the Edwards Aquifer Authority in a recent webinar

Designing and Capitalizing Durable Water Solutions

Quantified Ventures has a track record of working with companies, governments, organizations, and passionate people to develop and deploy flexible, outcomes-based solutions to water quality and quantity challenges.

This includes co-launching and scaling the Soil and Water Outcomes Fund, to speed the adoption of climate-smart conservation agriculture while providing financial benefits for participating farmers, communities, and outcomes purchasers.

And we are expanding our work with partners throughout the Colorado River Basin to design and advance multi-benefit water supply and demand management projects, including leveraging State Revolving Funds and other financing for drought-resilient agricultural practices.

Outcomes-based financing and public-private partnerships can deliver novel solutions to water challenges because parties align their focus on shared outcomes, share the risk and rewards, and enable more flexibility in both solution structure and funding mechanisms. Outcomes-based financing offers a more transparent, cost-efficient way to break through stalemates and move beyond the status quo.

When public and private actors work with Quantified Ventures to develop outcomes-based solutions, our shared focus on predicting, measuring, and reporting outcomes ensures the collection of key project data. With that data we develop a feedback loop with our collaborators that helps to iteratively evaluate and improve the environmental and social outcomes of a project. The transparency, flexibility, and ability to apply multiple mitigation and adaptation techniques efficiently and impactfully often opens the door to new sources of capital for projects.

The current abundance of federal and state funding for climate resilience and infrastructure presents significant opportunities for environmental and resilience programs, organizations, and enterprises.

The fact remains that it can be difficult to position your project or organization to secure some of this funding, and to administer it over time. Furthermore, it is critical that we leverage these new funding options to catalyze solutions that can stand on their own two legs and not be solely reliant on public funding. In the water sector and beyond, Quantified Ventures designs and capitalizes solutions that enable our partners to tap into public funding now and set an enterprise or program up for future growth by engaging other capital sources and partners.

The question we ask ourselves is how can we leverage available public funding and make it revolve, creating long-term solutions and lasting impact? Through outcomes-based financing, we’ve created revolving funds that support environmental restoration projects, then replenish via outcomes monetization. We’ve also organized the creation of local intergovernmental authorities formed specifically to coordinate funding streams, share staff capacity, and win supplemental public and philanthropic grants.

Outcomes-based solutions can help find a balance between growth and heritage, whether by structuring alternative business propositions for open lands or incentive programs for developers to incorporate more green spaces. Similar “third way” options can be structured for our precious water resources, by aligning incentives for shared stewardship between municipal users and agricultural producers or capturing the economic value of restoring historic spring flow.

These are all tools that can be deployed to help address the western water crisis. We look forward to working with the many committed public agencies, philanthropic organizations, and private entities working to develop innovative financial and programmatic solutions to our water crisis.